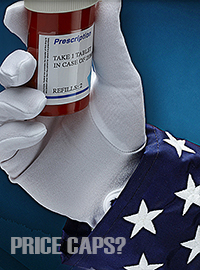

| Drug Price Controls Would Compound a Government-Made Problem |

|

|

By Ben Boychuk

Thursday, September 24 2015 |

Price controls and caps are always a bad idea. So when a candidate for president of the United States starts talking about the government setting prices for prescription drugs, it’s always a good idea to cast a cold eye. When two candidates for political office advocate price caps on prescription drugs, that’s when real trouble starts. Hillary Clinton on Tuesday outlined a proposal to combat “price gouging” that would cap the price of prescription drugs at $250 a month and empower Medicare to “negotiate” prices with drug makers. She would also require firms to put a certain percentage of their profits into R&D — which would guarantee an offshore exodus of R&D and manufacturing jobs. She was responding to a story about an obnoxious former hedge-fund manager turned pharmaceutical company CEO named Martin Shkreli, who last month paid $55 million for the rights to a 62-year-old anti-parasitical drug and promptly raised its price by 5000 percent. Shkreli’s company, Turing Pharmaceuticals, is attempting to capitalize on the growing specialty drugs market. Specialty drugs include medications for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, hemophilia and HIV, as well as “orphan” conditions such as growth hormone deficiencies. As its name would suggest, specialty drugs aren’t cheap. Often there are no generic alternatives. Socialist-Democrat U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders has been talking about price controls — including most of the ideas Clinton unveiled this week — since he kicked off his campaign this summer. Earlier this month, Sanders introduced a futile piece of legislation that would, among other things, cancel a pharmaceutical company’s “government-backed monopoly” — that is, its patent — on a drug if the company is “found guilty of fraud in the manufacture or sale of that drug.” These are “solutions” that only people who thought ObamaCare didn’t go far enough could love. It was government intervention that got us into this mess. It was ObamaCare that compounded the specialty drug cost crisis. ObamaCare puts a cap on out-of-pocket expenses for prescription drugs — $12,700 for a family, $6,350 for an individual. Sanders and now Clinton argue that if the cost of specialty drugs continues to rise unabated, government has an obligation to regulate costs to ensure drugs remain affordable. What’s wrong with that? Price cap controls don’t work, that’s what. Fixed costs tend to waste resources and encourage producers to limit supplies. Richard Nixon imposed wage and price controls on certain manufactured goods such as steel in the early 1970s during an economic downturn. It was a disaster. Manufacturers started laying off workers and closing plants because they couldn’t — and wouldn’t — sell at a loss. Price caps also discourage innovation. Why pour hundreds of millions into developing new drugs if you may not see much of a return on investment? Developing new therapies is expensive and time consuming, thanks largely to antiquated Food and Drug Administration rules. The Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD) says the cost of developing a prescription drug that gains market approval is a jaw-dropping $2.6 billion. “Drug makers must recoup the costs of development and R&D failures before a successful drug goes off patent,” the Wall Street Journal argues in an editorial Wednesday. “And it’s remarkable how far the pharmaceutical debate has shifted in a few years from an industry that allegedly couldn’t innovate and drugs whose benefits were too modest for the price. Now the political class is fretting because the benefits are transformative and costly.” That’s certainly true of new drugs. But what about drugs whose patents expired decades ago? Shkreli bought exclusive rights to market Daraprim, the brand name for pyrimethamine. The drug is used to treat toxoplasmosis, a life-threatening parasite infection that can afflict babies, the elderly and AIDS patients. Only one company in the United States manufactured Daraprim until Shkreli bought it, even though the patent has been in the public domain for years. In other words, he played by the rules of a rigged game. With exclusive rights in hand, Shkreli raised the price of Daraprim from $13.50 a pill to $750 a pill overnight. A six-week course of treatment for toxoplasmosis that cost around $600 yesterday would suddenly cost you the equivalent of a new Toyota Camry. But health care isn’t the same as purchasing a car. And in this instance, very few patients would have the resources to pay a five-figure sum for a drug. More often than not, they’ll go through Medicare, Medicaid or the state. In short, they won’t pay directly — but the taxpayers will. “The drug was unprofitable at the former price, so any company selling it would be losing money. And at this price it’s a reasonable profit. Not excessive at all,” Shkreli said. He reversed himself this week in the face of a public backlash, saying the company would lower Darprim’s price, but he didn’t say by how much. Ninety-nine times out of 100, “price gouging” is simply a seller’s way of adjusting for changes in supply and demand. States have imposed laws against supposed price gouging in the aftermath of natural disasters. But as any student of the free market knows, raising prices after a disaster is one of the best ways to guard against scarcity. If the price of gasoline, say, is held artificially low, people will make a run on service stations. Very soon they will be out of gas, with future supplies uncertain. It’s hard to see how raising the price of a drug by 5000 percent overnight is not one of those rare instances of price gouging. Like Plunkett of Tammany Hall, Shkreli saw his opportunity and he took it. The problem is, most Americans believe prescription medications are different from most products — and they are. You can put off buying a new car or TV, but you can’t skimp on drugs that may save your life. A Kaiser Family Foundation poll in August found nearly three-quarters of Americans surveyed believe drug costs are “unreasonable.” What’s more, 83 percent said the federal government should intervene somehow. In a divided nation, there is remarkable agreement among Republicans and Democrats on this question. I have a personal interest in this debate. My son has a chronic ailment that requires daily human growth hormone injections to treat. He will need those injections for at least the next five years. When we started his treatment two years ago, our coinsurance payment for a 25-day supply of the drug was $525. This year, our pharmaceutical management company switched the drug on us, and our out of pocket cost doubled. I have no idea what our cost will be next year, but if recent reports are any indication, I’m bracing for a 10 to 20 percent increase at minimum. For a free and open market to work the market must in fact be open and the consumer must have freedom of choice. Trouble is, the United States hasn’t had anything resembling a free market in pharmaceuticals in at least 45 years. Imposing price controls on top of an already-rigged system would only make matters worse. |

Related Articles : |