Obama’s Clean Coal Initiative: A Warning from California

The Los Angeles Times‘ front-page headline Tuesday comes across as remarkably upbeat: “California is ahead of the game as Obama releases Clean Power Plan.”

But the story’s lead paragraph reads more like a threat than a promise: “President Obama’s plan to cut carbon pollution from power plants over the next 15 years will force states to address climate change by pushing them to act more like California.”

The president cited California’s example when he announced the plan on Monday, recalling the smog that hung over the Los Angeles basin in the late 1970s and early 1980s. “You fast-forward 30, 40 years later, and we solved those problems,” Obama said.

Well, yes, we did — and it’s a good thing, too. But the president is conflating those clean-air rules with policies of a more recent vintage.

California has led the way in pushing utilities to adopt renewable energy from sources such as windmills and solar panels in lieu of natural gas and coal-fired plants. According to the Times: “In 2013, the most recent year available, nearly 19% of California’s electricity came from renewable sources, while less than 8% came from coal, according to the California Energy Commission. In January, Brown proposed an ambitious target of 50% renewables by 2030.”

The story doesn’t mention, however, that the Golden State ranks close to the top in terms of energy prices. It’s no coincidence that the cost of renewable energy in California increased by 55 percent between 2003 and 2013, as the renewable portfolio standard was being phased in. And costs will continue to rise, in no small part because the state Public Utilities Commission earlier this year ordered changes in California’s tiered pricing for electricity, moving from four tiers to two. As a result, the first tier rate will increase significantly, and the second tier rate will rise marginally.

The Times also reports that California is on track to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020 as required under AB 32, the “Global Warming Solutions Act” of 2006. Gov. Jerry Brown in January issued an executive order that would accelerate the mandate’s requirements, with the goal of reducing emissions by 40 percent from 1990 levels by 2030. Expect rates to go higher still.

Not surprisingly, Brown hailed Obama’s plan as “bold and absolutely necessary.”

But a new Manhattan Institute report by Jonathan A. Lesser of Continental Economics highlights the real consequences of California’s decarbonization efforts, some unintended, some not. Among Lesser’s key findings:

- California households’ electricity prices have risen as a result of the state’s renewable-energy mandates and carbon cap-and-trade program—and will likely continue to rise at an even faster rate in coming years.

- The aforementioned policies have created a regressive energy tax, imposing proportionally higher costs in certain counties, such as California’s inland and Central Valley regions, where summer electricity consumption is highest but household incomes are lowest.

- In 2012, nearly 1 million California households faced “energy poverty”—defined as energy expenditures exceeding 10 percent of household income. In certain California counties, the rate of energy poverty was as high as 15 percent of all households.

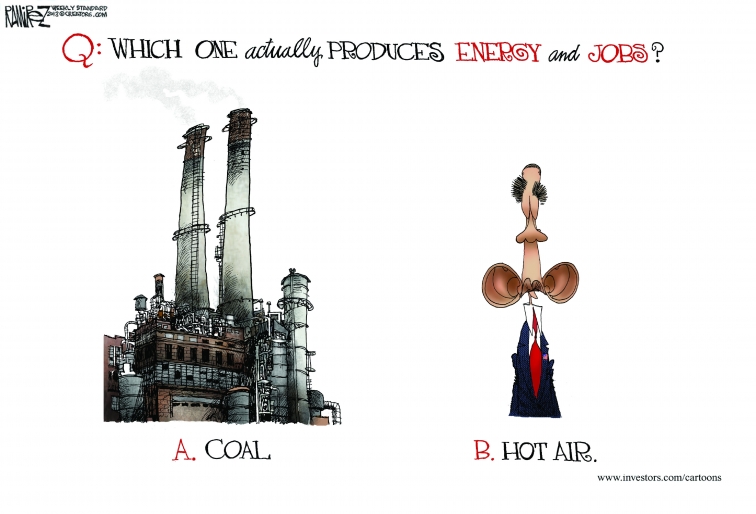

This is the model that President Obama lauds and his EPA wants to emulate. The EPA’s new regulations would mandate that states cut carbon emissions 32 percent from 2005 levels by 2030.

A tough Wall Street Journal editorial notes that the EPA’s final rule “is 9 percent steeper than the draft the Environmental Protection Agency issued in June 2014,” and opines: “The damage to growth, consumer incomes and U.S. competitiveness will be immense—assuming the rule isn’t tossed by the courts or rescinded by the next Administration.”

Steven F. Hayward, a professor of politics at Pepperdine University and an expert in environmental policy, observed in a post at Power Line on Monday, “By [EPA’s] own admission, full implementation of the emissions targets will avert only 0.018 degrees C of warming by the year 2100. I’m sure we’ll all notice that much change in temps!”

The final rule is nearly 1,600 pages long, and the regulatory impact analysis is nearly 400 pages, so needless to say it will take some time for the lawyers and wonks to sort everything out. But Hayward found an odd paragraph in near the middle of the impact analysis that led him to wonder if the government is putting us on:

As indicated in the RIA [Regulatory Impact Assessment] for this rule, we expect that the main impact of this rule on the nation’s mix of generation will be to reduce coal-fired generation, but in an amount and by a rate that is consistent with recent historical declines in coal-fired generation. Specifically, from approximately 2005 to 2014, coal-fired generation declined at a rate that was greater than the rate of reduced coal-fired generation that we expect from this rulemaking from 2015 to 2030. In addition, under this rule, the trends for all other types of generation, including natural gas-fired generation, nuclear generation, and renewable generation, will remain generally consistent with what their trends would be in the absence of this rule. [Hayward’s emphasis.]

Hayward poses a fascinating question: “if the electricity sector under this new regulation is going to unfold more or less along the lines of business as usual, why are we bothering with this regulation in the first place? Is the EPA seriously admitting that their regulation does nothing substantial at all, or that they’ve spotted a parade going down the street and decided to march at the head of it?”

The Wall Street Journal‘s editors encourage a vigorous legal challenge to the new rules, noting:

The Supreme Court did give EPA the authority to regulate carbon emissions in Mass. v. EPA in 2007. But that was not a roving license to do anything the EPA wants. The High Court has rebuked the agency twice in the last two years for exceeding its statutory powers.

“When an agency claims to discover in a long-extant statute an unheralded power to regulate a significant portion of the American economy, we typically greet its announcement with a measure of skepticism,” the Court warned last year. “We expect Congress to speak clearly if it wishes to assign to an agency decisions of vast economic and political significance.”

Congress did no such thing with the Clean Power Plan, which is a new world balanced on a fragment of the Clear Air Act called Section 111(d). This passage runs a couple hundred words and was added to the law in 1977, well before the global warming stampede. Historically Section 111(d) has applied “inside the fence line,” meaning the EPA can set performance standards for individual plants, not for everything connected to those sources that either produces or uses electricity.

When the EPA rule does arrive before the Justices, maybe they’ll rethink their doctrine of “Chevron deference,” in which the judiciary hands the bureaucracy broad leeway to interpret ambiguous laws. An agency using a 38-year-old provision as pretext for the cap-and-tax plan that a Democratic Congress rejected in 2010 and couldn’t get 50 Senate votes now is the all-time nadir of administrative “interpretation.”

“This plan is essentially a tax on the livelihood of every American,” the Journal‘s editorial concludes, “which makes it all the more extraordinary that it is essentially one man’s order.” As California goes, so goes the nation? Let’s hope not.

In an interview with CFIF, William Yeatman, Assistant Director at the Competitive Enterprise Institute’s Center for Energy and Environment, discusses the Obama Administration’s climate agenda, its all-out war on coal, the Keystone Pipeline project and the EPA’s assault on state sovereignty.

In an interview with CFIF, William Yeatman, Assistant Director at the Competitive Enterprise Institute’s Center for Energy and Environment, discusses the Obama Administration’s climate agenda, its all-out war on coal, the Keystone Pipeline project and the EPA’s assault on state sovereignty.

CFIF Freedom Line Blog RSS Feed

CFIF Freedom Line Blog RSS Feed CFIF on Twitter

CFIF on Twitter CFIF on YouTube

CFIF on YouTube